A Director’s Guide to Audience Perception

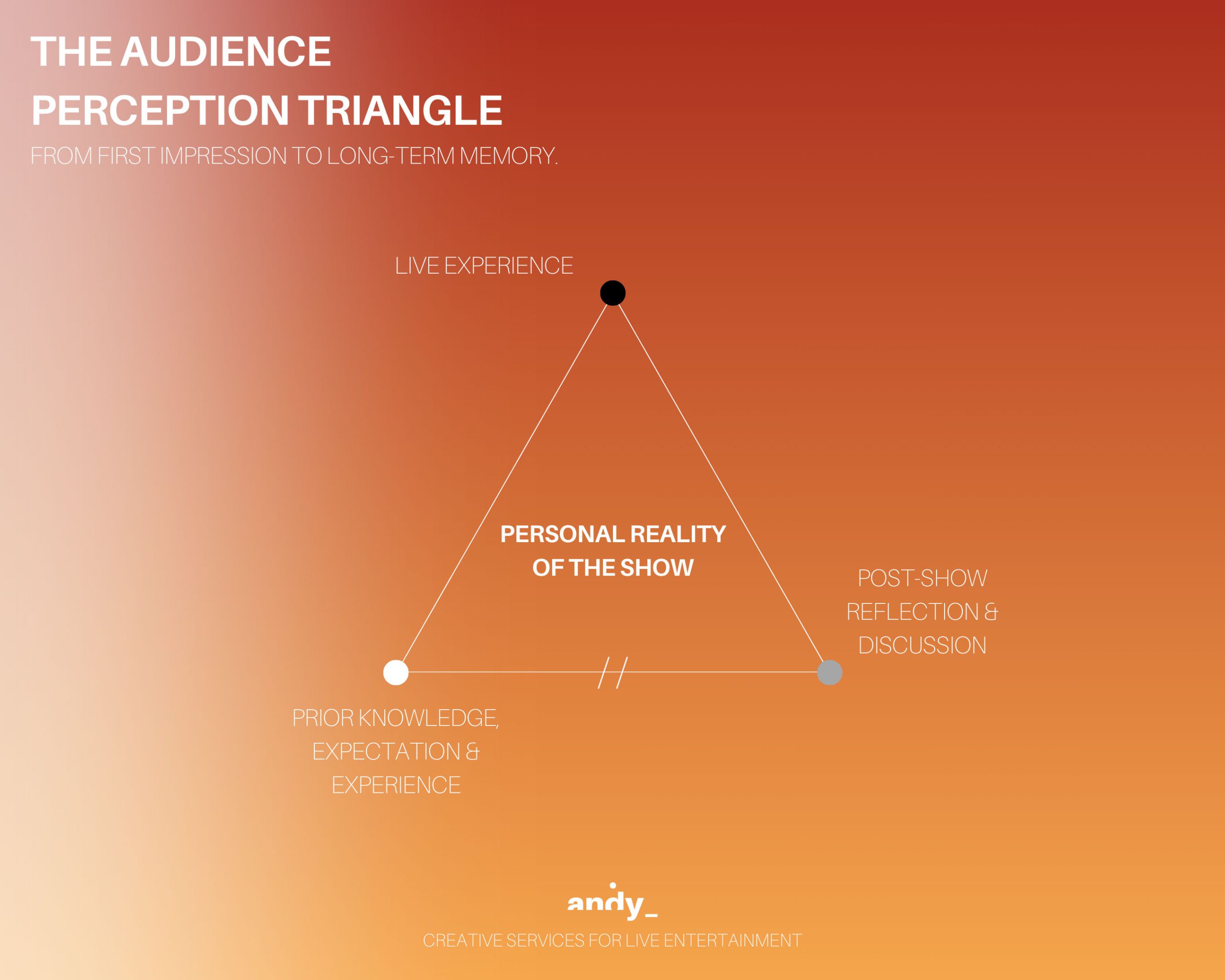

A performance never purely exists in isolation—it’s shaped by the people watching it. No two audience members see the same show, even when they sit in the same room, at the same time, watching the same performers. Each person arrives with their own expectations, experiences, and biases, filtering everything through their own perspective.

For show directors and creative leads, this isn’t just a theoretical idea—taking seriously our audience is both a challenge and an opportunity. If every audience member perceives a show differently, then directing isn’t just about controlling what’s on stage. It’s about designing an experience that actively engages multiple perspectives, rewards interpretation, and leaves room for discovery. In this respect, meaning is not just made by performers—it is actively co-constructed by the audience. Let’s dive into what this means.

1. Performance Is a Public Experience, But Not a Shared One

I know – this is a provocative take, because in event marketing, we talk about a show being a shared experience. Let me cook: because, while this is true, it couldn’t be further away from the truth. A full theatre doesn’t mean a unified experience. From a brand manager’s perspective: they want a shared experience and sell it as an asset. From a director’s perspective: this never happens for everyone at the same time! Every audience member brings a different background, knowledge base, and set of assumptions, shaping how they process what unfolds in front of them. Some will recognize references, while others will see the same moment in an entirely different light. Have you ever watched an episode of Ru Paul’s Drag Race together with a queer and a straight person, and noticed which references straight people have no eff’ing clue about? This is exactly it!

Example: Hamlet and the Question of Interpretation

A classic example is Hamlet. Some audience members might see it as the tragedy of a hesitant prince unable to act, while others read it as the story of a young man trapped in a corrupt political system. Scholars have debated for centuries whether Hamlet is indecisive or methodically strategic. The performance style, the actor’s choices, and even the cultural moment in which it is staged all influence the audience’s perception. A director must recognize that no matter how clearly they define their vision, the audience will always bring their own reading, which is a mix of eduction, projection, desires, amongst many more, which translate into a show’s creative vectors.

Takeaway for Creative Leads: Instead of fighting this multiplicity, use it. Direct in a way that invites different readings rather than closing them off.

2. Understanding a Show Is a Process, Not a Moment

People don’t just absorb a performance in real time—they continue piecing it together afterward, discussing it, rethinking key moments, and comparing interpretations with others. Meaning isn’t delivered instantly; it evolves as audiences reflect, debate, and recall the experience later.

Example: Waiting for Godot and the Long Echo

When Waiting for Godot first premiered, many critics dismissed it as nonsensical, while others saw it as a profound statement on human existence. Over time, its reputation changed as new interpretations emerged—existentialist, political, even comedic. Each production adds new layers, shaped by the time and place in which it is staged. For example, a production in apartheid-era South Africa used it as a metaphor for racial oppression, while others have seen it as a reflection on war, economic crisis, or personal despair.

Takeaway for Creative Leads: Craft moments that stick with audiences beyond the curtain call. Think about how ambiguity or layered meaning might allow a production to unfold in the minds of the audience long after they leave the theatre.

3. Uncertainty Is an Asset

Live performance is unique because it unfolds in real time, forcing audiences to process information as it happens. Unlike film, where viewers can pause and rewind, theatre exists in the moment, leaving gaps that audiences must fill in on their own. This uncertainty creates tension, engagement, and even excitement. This makes performance an inherently unstable source of knowledge—it’s temporary, fleeting, and highly dependent on memory, discussion, and post-show reflection to solidify meaning.

Example: The Unpredictability of Sleep No More

Immersive theatre productions like Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More or The Burnt City embrace uncertainty by allowing audiences to navigate the performance space freely. Two people might experience entirely different shows based on which characters they follow, which rooms they enter, and what details they notice. This kind of storytelling forces the audience to become active participants, making meaning from fragments rather than receiving a linear narrative.

Takeaway for Creative Leads: Not every show has to be immersive, but creating space for mystery and discovery keeps an audience engaged. A multi-sensory dramaturgy, where, instead of achieving a holistic sensory experience, certain desires remain unaddressed and amount to unresolved tensions making a show linger in the mind.

4. Emotions and Ideas Are Not Opposites

There’s a common assumption that some performances are “intellectual” while others are “emotional,” as if the two are separate. In reality, the most powerful performances do both—using emotional intensity to provoke thought, and intellectual depth to heighten feeling.

Example: A Chorus Line and the Emotional Power of Structure

A Chorus Line works because it balances raw personal stories with a larger philosophical question: What does it mean to dedicate your life to performance? The show could have been purely sentimental, but by structuring it as a competition where dancers are both emotionally vulnerable and professionally at risk, it adds an intellectual weight to the experience. The audience isn’t just moved by individual stories—they’re also forced to think about the industry, the nature of art, and the cost of success.

Takeaway for Creative Leads: A great show doesn’t just make people feel—it makes them think about why they feel that way. Use structure, contrast, and pacing to blend emotion and intellect into a single experience.

Performance isn’t about transmitting a single idea—it’s about creating an experience that lingers, provokes, and evolves. The most compelling shows aren’t the ones that explain everything, but the ones that make audiences want to keep thinking, talking, and feeling long after the curtain falls.

Checklist: How to Make Performance Live Beyond the Moment

✅ Does the show allow for multiple interpretations? (Hamlet)

✅ Are there moments designed to spark discussion and reflection? (Waiting for Godot)

✅ Does it embrace unpredictability, drawing audiences into the present moment? (Sleep No More)

✅ Is it both emotionally engaging and intellectually stimulating? (A Chorus Line)

✅ Will audiences leave with something unresolved—something that stays with them?

FOR THE NERDS

We’ve been talking about Epistemology.

Epistemology—the study of knowledge, belief, and how we come to understand things—plays a crucial but often overlooked role in performance. When applied to performance, epistemology isn’t just about what we know; it’s about how we know, what counts as valid knowledge in a theatrical or live event, and how different perspectives shape that knowledge. Again, it’s about a process – how do we come into knowing?

What Is the Epistemology of Performance?

The epistemology of performance examines how knowledge is created, exchanged, and interpreted in live events. It considers:

- How audiences perceive and process performance – What does an audience member actually “know” about a show while watching it? How do they make sense of what they see?

- How interpretation is shaped by personal and cultural context – Does prior knowledge change how a performance is understood?

- The role of liveness and uncertainty – What does it mean to “know” something in a medium where events happen in real time and can’t be revisited exactly the same way?

- How meaning is constructed over time – Can someone say they “understood” a performance immediately, or does understanding emerge over reflection and discussion?

- The relationship between private perception and public discourse – If every person has a unique experience of a performance, where does collective meaning come from?

Why Does This Matter for Show Directors and Creative Leads?

Understanding the epistemology of performance means recognizing that a show is never just what is presented—it is also how it is received. Directors and creators who embrace this idea can:

- Craft performances that allow space for interpretation rather than dictating a single meaning.

- Play with ambiguity and uncertainty to create a richer, more dynamic audience experience.

- Think beyond the moment of performance, considering how a show will live in the audience’s memory and discourse afterward.

- Recognize that every audience will “know” the show differently—and that’s not a flaw, but a fundamental part of how performance works.

In short, the epistemology of performance tells us that theatre and live events don’t just communicate ideas. They ask questions, create uncertainty, and invite audiences to participate in meaning-making. It’s not about delivering a single truth—it’s about creating an experience that leaves people thinking, questioning, and engaging long after the performance ends.

Do you know the key concepts of performance epistemology and how they can help making your work more interesting?

If want to read more about epistemology in performance, grab The Problems of Viewing Performance: Epistemology and Other Minds (2021) by Michael Y. Bennett, or, much more theoretically, Performance Epistemology: Foundations and Applications argues that understanding a performance—like any skilled action—depends on the interplay between perception, interpretation, and the audience’s own cognitive and cultural frameworks.